One of the greatest biologists of the 20th century, John Maynard Smith, will be remembered for his contributions to genetics and evolutionary biology, and by Humanists UK as a Patron of Humanism.

One of the greatest biologists of the 20th century, John Maynard Smith, will be remembered for his contributions to genetics and evolutionary biology, and by Humanists UK as a Patron of Humanism.

He was deeply committed to his work and to making scientific ideas accessible, and inspired many younger scientists. He continued writing and research well after normal retirement age, publishing his last book, Animal Signals , the year before he died. He will also be remembered for his good humour and for the affection he inspired amongst colleagues and students.

In a Humanist News interview published in 2001 (see below), he described how exciting he found “the mixture of extreme rational science, blasphemy and imagination” in the essays of J B S Haldane he read as a schoolboy. He said of religion: “I am tolerant because religious institutions facilitate some very important work that would not get done otherwise, but then I look around and see what an incredible amount of damage religion is doing…It would not matter so much that people believe lies, but when they go out and beat other people up because they believe different lies, that’s another thing.”

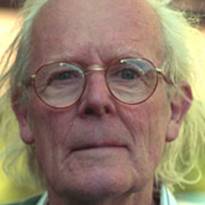

John Maynard Smith talking to Humanist News in Autumn 2001

Best known for his work as a biologist and evolutionist,Humanists UKsupporter Professor John Maynard Smith has spent the last ten years researching the evolution of bacteria, and antibiotic resistance. He is highly respected for writing intelligent but accessible books on biology such as ‘The Origins of Life’ and ‘The Major Transitions of Evolution’. His life reveals a man who has himself undergone several major transitions in thinking and ideology during the course of his lifetime.

You became an atheist whilst quite young – can you talk about this first major transition in your thinking?

I was brought up in the Church of England, which is more of a social club than a religion, and believed in Christianity until I was about 14 or 15 when, largely as a result of learning about evolution and Darwin , I started having doubts. The really decisive moment occurred at school. I was at Eton , which was a really odious school then, snobbish and anti-intellectual – although not univer sally so, as there were some excellent masters, and I was taught mathematics brilliantly – but the boy culture of my youth was elitist. They considered themselves to be a separate breed. By the time I was 15 I had come to greatly dislike this. The one person my schoolmasters really hated was J. B. S. Haldane – because he was an atheist, a socialist, a republican and divorced – and so I thought I had better read this guy. To their credit, his essays were in the school library, so I took out a book called Possible Worlds , and it completely blew my mind. His mixture of extreme rational science, blasphemy and imagination, was a way of thinking that I had never met before.

I remember sitting there as a boy of 15 reading the title essay, and that was it! It got me interested in evolution and alternatives to religious interpretations of the world, but it was also enormously encouraging to know there were people like that in the world because up until then I had been exposed to ideas that didn’t very much appeal to me. Of course, twenty years later I was to work with Haldane, but a lot was to happen before that.

Where did your new-found atheism lead you next?

Well, I went to Cambridge to read Engineering. Cambridge was a complete liberation for me. But to set the scene – back in the 1920s and 30s, even before that, eugenics was almost a kind of religion among the intellectual middle-class. There were some people, like the Webbs, who founded the Fabian Society, and Marie Stopes, who was important for women’s liberation, who were out-and-out eugenicists. Then there were people like Haldane who believed that men were not all created equal, that there were differences, and that some of those differences were genetic, but considered that rather than change the people to fit the world you should change the world to fit the people. He believed we should devise a society in which people with different talents could be happy and productive. Yet Haldane too was very interested in genetics.

The rise of Hitler transformed things, because people suddenly saw where eugenic ideas could lead. By 1936-40, before the war even, eugenics was coming under attack because of this connection with Nazi ideals. People knew that Hitler was violently anti-Semitic and that Jews were being thrown out of their jobs and persecuted, and so on. I knew that as a boy of 17. And we knew Hitler preached that the Aryans were the super-race, and it was this that really changed people’s ideas about eugenics. So, after Haldane, it was the rise of Hitler that had a dominant effect on many of my generation in the 1930s. And of course the effect was to turn us into Communists.

Why did you become a Communist?

Until about 1938 I was a pacifist. Many of my generation were pacifists because our parents, who had been through the First World War, had told us it was so awful. In my case my mother refused to talk about it at all, which left a far deeper impression than if she had. I was a pacifist until I went to Germany in 1938, where it became perfectly clear that there was going to be a war, and that pacifism was not going to stop Hitler. I came back to England in a state of complete confusion, convinced that my pacifism was wrong, and the one group in Britain at that time who were saying we have got to unite and oppose Fascism, were the Communists.

For me this conflict between, on the one hand, the Marxist belief that “man’s being determines his consciousness” – that if you reform society you will transform people, who will become cooperative and helpful to one another as a consequence – and, on the other, the genetic view that people’s characters are determined by some sort of inner genetic nature, has been a continual source of conflict since 1935. Communists were not just anti-Nazi, they were preaching greater equality, and the discontinuation of the British Empire as well. In a sense it was my hatred of Eton that drove me to the party, along with my Asian friends at Cambridge who had convinced me that the British Empire was not all that it was cracked up to be. It was this concern with social inequality, imperialism and Hitler that appealed. The fact that that the Communists were besotted by the Soviet Union , which was being ruled by a paranoid lunatic at that time, somehow escaped them and me. Something that people often ask me is how could I have supported the Gulags? The answer is, quite simply, that I didn’t believe in them. There was this built-in defence among Marxists that anything that was said against the Soviet Union was a capitalist lie. And, you see, I believed them.

Why did you did leave the Communist Party?

The real cause of the break was something completely and profoundly trivial. It was to do with Lysenko. You see Lysenko was holding what was a manifestly false view about genetics, he was anti-Mendelian, and anti-genes. He was a total Lamarckist, in that he believed that acquired characteristics were inherited and so on.

The point about Lysenko was that while I wouldn’t believe in the Gulags I had to believe in Lysenko because he was being published by the Russians

themselves. It was the crack in the dyke, so to speak. And it was not just that he was scientifically wrong, but that the scientific error emerged directly from Marxism. He was being supported by the Communist Party, who I felt had no right to make decisions about scientific issues. But the central committee of the Soviet Union was backing him, and as a consequence many perfectly good scientists lost their jobs, and in some cases their lives. And that was what we couldn’t support.

The Lysenko case is very revealing because, firstly, it promised a quick fix in that if acquired characteristics could be inherited you could change society much faster, and I think the Communists wanted to believe there was a quick fix for society, but more than that, Marxist philosophy is dialectical and so it is deeply hostile to the notion that a gene can affect development but development can not affect the gene. So Lamarckism is a natural for Marxism. For me it was an intellectual puzzle – I couldn’t have things both ways. But it took a year or two to reach that conclusion, and I even spent six months trying to do a Lamarckian experiment to demonstrate inheritance of an acquired kind, but of course it failed. It was the beginning of a process of questioning which ultimately would lead me to leave the Communist Party.

I didn’t actually leave until the Russians entered Hungary , but I stopped working for the Party by 1950. It was a loyalty thing really, the longer you stayed with the Party the harder it was to leave because one was abandoning one’s friends. But in 1956 I thought I could no longer be associated with what was going on.

What is your attitude to religion now?

Ever since reading Possible Worlds I have been an atheist, and a semi-conscious atheist before that. I think there are two views you can have about religion. You can be tolerant of it and say, I don’t believe in this but I don’t mind if other people do, or you can say, I not only don’t believe in it but I think it is dangerous and damaging for other people to believe in it and they should be persuaded that they are mistaken. I fluctuate between the two. I am tolerant because religious institutions facilitate some very important work that would not get done otherwise, but then I look around and see what an incredible amount of damage religion is doing.

An unfortunate thing about human beings, which I do think is part of our genetic make-up to some extent, is that we can be indoctrinated. Make us wear silly hats, sing silly songs, and give us a separate accent and separate terminology – I’m thinking of Eton again here – and we begin to bond together against other groups. And as Plato knew, you can make people believe any lie you like. It wouldn’t matter so much that people believe lies, but when they go out and beat other people up because they believe different lies, that’s another thing. So I have mixed feelings about religion: it can lead people to do noble and self sacrificing things and kindly things, but can also lead them to behave quite abominably.

Does this make more sense, perhaps, at a socio-biological level?

Yes, what particular things you believe is clearly cultural. There isn’t a gene for being Muslim rather than Christian – that would be absurd – but the fact that we can be indoctrinated by a culture of this kind, and become loyal and friendly to people who share our myths and culture and hostile to people who do not is, I think, something which humans clearly do. I don’t want to say it is genetically determined, I don’t like that phrase, but it is a feature of human beings. Clearly you can reject indoctrination, but only if there is some alternative culture out there which you can join. You couldn’t do it entirely on your own.

Do you see a conflict between providing for human needs and our desire to conserve nature?

Well, I certainly don’t want to see any decrease in biodiversity. The problem is that we cannot sustain an ever-increasing growth in population. We are bound to hit disaster sooner or later, and probably sooner rather than later. However, I think Malthus got it wrong when he said that the human population has an inherent

tendency to increase and will continue to do so until it is brought to an end by starvation, overcrowding and so on. It turns out that it may in fact be the other way around and that, if you improve people’s economic lot there will be a reduction in the birth rate. If we can only get ahead and actually improve people’s lives, we can prevent the population from increasing, and cope with the other problems of the world. But if poverty and lack of education continue then we have got nothing but disaster ahead.

What do you see as the most exciting work ahead in science?

We are living through a revolution in genetics, developmental genetics has absolutely exploded and has brought about an enormous increase in our understanding of how development works. But as yet it is not quite clear what the take-home message is.

The thing that scares me, and scares me a lot, is that while we are technically able to cure diseases it is exceedingly expensive and technically very difficult to do so. The result of those two equations may be that we are going to have one world for the rich and one for the poor – a world of genetic engineering, in which we actually alter people’s genetic constitutions, could finish up like H. G. Wells’ Time Machine – you remember, the Warlocks and so on – with a class difference based on genetic difference. While I don’t want to stop medical research I do think we need to consider deeply the social implications of the cost of genetic treatment. We have to recognise that the Heath Service is not going to get cheaper, but that it is enormously important that these treatments are available on the National Health.

There are places where couples who intend to marry are given genetic counselling for diseases which are prevalent in their community, and are denied the right to marry if they test positive. What is your opinion on this?

I go back to Haldane, and in this you will realise how much I am his child. Haldane thought we should be test ed when young and given a badge or jewel which would identify any harmful genes we were carrying. Then, if you were at a party and met someone you rather fancied but noticed that they were wearing the same badge as you, you would not get too involved. But ultimately this is not the answer because by avoiding marriage between two people who are carrying the same recessive gene you are removing the natural selection against those harmful genes, and their frequency in the population will increase. Certainly I’m all for the treatment of diseases, but it is a general fact that the more we do so the more we will find a rise in the frequency of genetic disorders. So sooner or later we are going to have to either transform genes in the gene pool, or select against deleterious genes at the blastacyst stage. I don’t have any moral repugnance about selecting blastacysts, but both methods are expensive and difficult.

I’m afraid I tend to have copped out on this one all my life, the cop out being “it’s not happening all that fast so we can afford to wait another 50 years, and by then we will understand so much more about genetics that we will be able to cope, but right now let’s try to get on and stop the birth of defective children”. But I know I’m just passing the problem on to my descendants. However, I think that if my wife and I knew we were both carrying the same recessive gene for some harmful disease we would want to do what is perfectly possible at the moment, which is to avoid the birth of a child that was homozygous for that gene by selecting on blastacysts. Obviously, once a child is born with a defect you must do what you can so that the child’s life is as normal and happy as possible. But if we can avoid a child being conceived with that defect then I think we should.

Would you like say any more on the tension within the nature / nurture debate?

There has been fierce criticism of genetic determinism. It is seen as a deeply wicked attitude, which it very probably is, but I don’t know of any geneticists who actually hold that view. Holding the view that human beings have genetic tendencies does not mean that you believe those tendencies are inevitable. Some may be more difficult to alter than others, eye colour for example, but something like religious belief is only determined to a minimal degree. What I think is determined is the capacity to hold such beliefs but not what you believe or whether you believe it or not. Similarly, having a genetic tendency towards something is not the same as finding “the gene” for something.

On the other hand I get equally irritated by my social scientist acquaintances who have what I call atabula rasa view of human beings and think that they can believe anything, do anything, or be culturalised to do anything. It’s rubbish. And taking a rigid view on the side of either social determinism or genetic determinism is plain silly. We just have to realise that we live in a far more complicated world.