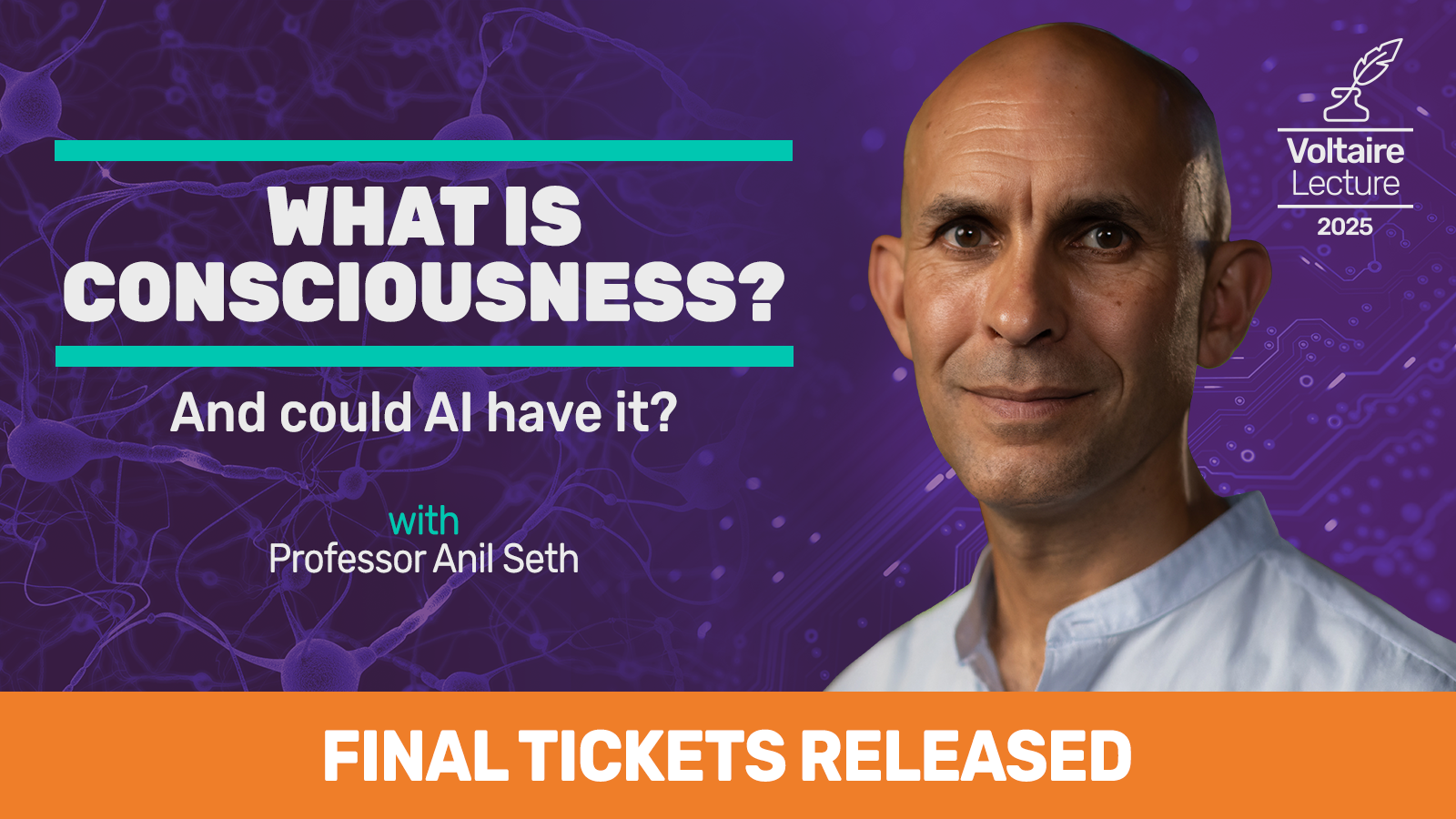

Ahead of the Voltaire Lecture on 31 October, we spoke with Professor Anil Seth, neuroscientist and Professor of Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience at the University of Sussex, about the themes of his upcoming talk.

Hello Anil! In your lecture, ‘What is consciousness? And could AI have it?’, you’ll be exploring one of the greatest mysteries in science and philosophy – the nature of consciousness itself.

Rather than trying to ‘solve’ it head-on, you talk about ‘dissolving’ the problem of consciousness step by step. Could you give us a preview of how this approach works, and why you think it helps demystify consciousness?

The basic idea, which has been around for a long time, is to treat consciousness a little like how scientists came to understand life. Instead of treating it as one big scary mystery in search of a single Eureka! solution, divide and conquer.

Not so long ago, many people thought that life was beyond the reach of science. But that sense of mystery dissolved as biologists got on with the job of explaining properties of life, like metabolism, homeostasis, and reproduction.

I suggest the same strategy will bear fruit for consciousness too. Instead of bashing our brains repeatedly against the hard problem of how physical processes might give rise to conscious experiences, let’s instead focus on explaining the properties of consciousness in terms of biology and physics. This is what I like to call the ‘real problem’ of consciousness. Maybe we won’t fully dissolve the hard problem this way, but only time, and effort, will tell.

One idea you highlight is that our conscious experiences – of the world around us and of ourselves within it – are built on the brain’s perceptual predictions, all rooted in a fundamental drive to stay alive. How does this survival imperative shape what we perceive and feel? In other words, why is being alive so integral to the way we experience reality?

The idea of the brain as a prediction machine is one powerful way to address the ‘real problem’ – to build explanatory bridges between what happens in our brains and what happens in our conscious minds. And the more you explore this idea, and follow where it leads, the more – at least to me – a deep connection with life emerges.

The basic idea here is that the reason brains are prediction machines in the first place is to keep the body alive, and this fundamental drive to survive goes right down into the furnaces of metabolism within each and every cell. To put it another way, the predictions our brains make about the world around us are all deeply inflected by their relevance for our survival prospects. We experience the world around us, and ourselves within it, with, through, and because of our living bodies.

‘The predictions our brains make… are all deeply inflected by their relevance for our survival prospects. We experience the world around us, and ourselves within it, with, through, and because of our living bodies.’

You also write about how widely consciousness might exist in non-human animals. Do other animals experience consciousness too, in your view, or is our human level of self-awareness truly unique?

Two things can be true at the same time. Yes, I believe other animals are conscious, though there are very difficult questions about which animals fall within this charmed circle. And yes, human consciousness, and human cognition, is also unique. We humans have a knack for language and music and number and maths that other species seem to lack. There are some fascinating ideas out there about how these distinctively human abilities may be rooted in how our brain has evolved the ability to combine things in new ways – I’m thinking here of brilliant work by the French neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene.

Whether self-awareness is distinctively human is a difficult question, in part because the ‘self’ is not one thing. For example, the ability to recognise oneself in a mirror seems rather rare (though not uniquely human), while the ability to make plans for the future and to distinguish self from other seems much more widespread.

When it comes to machines, you’ve suggested that consciousness might require more than just raw computing or ‘information processing’ – it could depend on qualities unique to living organisms. What do living brains have that digital machines lack? And does this mean a non-biological AI might never truly feel conscious, no matter how ‘intelligent’ it becomes?

This is one of the key questions for our time. There’s no doubt that machines can now give powerful impressions of being conscious, most obviously by talking to us, and sometimes even by talking to us about consciousness. But there are many differences between embodied, embedded brains, and the abstract algorithmic acrobatics of large language models. My hunch is that these differences do make a difference when it comes to consciousness, and that computers – AIs – might at best simulate but never instantiate conscious experiences.

Certainly, we must be careful not to conflate consciousness with intelligence. Consciousness is fundamentally about feeling, whereas intelligence is fundamentally about doing. Just because the two properties go together in us (at least we like to think we’re intelligent – some other species might demur) doesn’t mean they must always go together.

On a related note, there’s a lot of excitement (and hype) around artificial intelligence right now. From your perspective, are today’s AI systems – like those clever chatbots that mimic conversation – anywhere close to being conscious? What do you think would be required for an AI to actually have a conscious experience, as opposed to just faking it?

My opinion on this is indeed that things like chatbots are not currently conscious and won’t become conscious even if they get better at chatting, which they will. One way of putting your second question is: how brain-like does an AI have to be, in order to move the needle on the prospects for it being conscious? Here, I think we need a certain collective humility. We don’t know what the sufficient conditions are for consciousness.

Personally, I worry more about accidentally creating conscious artefacts in things like ‘brain organoids’ (a branch of synthetic biology) than in the next iteration of ChatGPT.

‘There are also more insidious challenges, including diminishing our appreciation for the wonder of what being a human being really involves.’

If in the future we create an AI that can convincingly pretend to be conscious, what ethical challenges would that raise? For instance, should we treat such an AI as if it has feelings or rights? Or should we be more concerned about how easily humans might be fooled by a machine with no real inner life?

There’s lots to worry about here. Some people make the tempting argument that since we don’t know the sufficient conditions for consciousness, we should ‘play it safe’ and treat conscious-seeming things, like chatbots, as if they are in fact conscious. The AI firm Anthropic has adopted a policy like this, going as far as hiring people to look after the ‘welfare’ of its chatbots. This argument is admittedly tempting, not least because we humans have too often been on the wrong side of history when it comes to questions of how far to extend our circle of moral concern. It also echoes Alan Turing’s strategy in his famous ‘imitation game’, about when to attribute ‘thinking’ to a machine. But I do not think this is the right way forward in the case of consciousness.

We have good reasons to doubt that current AI is conscious, and treating unconscious AI as if it is conscious can lead to many problems, including – as you mention – increased risks of psychological exploitation. There are also more insidious challenges, including diminishing our appreciation for the wonder of what being a human being really involves. As the sociologist Sherry Turkle memorably put it: ‘technology can make us forget what we know about life.’

You’ve famously described our perceptual reality as a ‘controlled hallucination’ generated by the brain. Can you explain what this means? How does this idea help us understand things like optical illusions – and even why two people might experience the same event so differently?

This goes back to the idea of the brain as a prediction machine of some kind. Intuitively it might seem that we experience the world in some direct way, as if it pours itself into our minds through the windows of our senses. But how things seem is not how they are. The story I favour, backed now by lots of evidence, is that our conscious experiences are inferences or ‘best guesses’ about what’s going on.

In this story, the brain is continually making predictions about the causes of sensory signals, and updating these predictions based on the sensory signals that it encounters. This means that our perceptual experiences are top-down active constructions, and that we can think of perception as a kind of ‘controlled hallucination’. One striking implication of this theory is that, because we all have different brains, we will all experience things in different ways, even for the same shared reality.

I’m currently working on one project – The Perception Census – which aims to understand just how deep this ‘perceptual diversity’ runs. We’ve collected data from about 40,000 people in over 120 countries. I’m hoping we’ll have some results soon.

Alongside your research, you’re well known for bringing the science of consciousness to a broad audience – through your TED talk and your bestselling book Being You. Why do you think it’s important to engage the public in scientific discussions about consciousness? What do you hope people will take away from learning how their own minds work?

Oh my, there are so many reasons. The beautiful thing about consciousness research is the way in which it brings together so many things of both interest and importance. The nature of consciousness is one of the greatest remaining mysteries in all of science and philosophy. As we grapple with it, we write new chapters in the millenia-long story of how we understand our place in the universe. It is also a mystery that matters right here and right now, for all sorts of reasons. We’ve touched on some of these already, such as which other animals (or AIs!) are conscious. A deeper understanding of consciousness will also have significant impact in psychiatry, neurology, law, and much more besides.

Critically, the science of consciousness does not itself specify what these impacts will be. How the insights from the science end up shaping society is something that stakeholders of all kinds within society need to discuss together. Public engagement is not simply about dissemination. It is, or rather should be, a truly two-way process.

The last thing to say here is that understanding more about how our minds work can, I believe, help us all to lead happier and more socially-positive lives – to be better humans.

‘We should base moral decisions on reason, evidence, and compassion rather than on divine or supernatural laws.’

Are you a humanist? If so, what resonates with you about the humanist approach to life?

I am definitely humanist-friendly! I’m on board with the idea that we should base moral decisions on reason, evidence, and compassion rather than on divine or supernatural laws. I am also a strong believer in science, though I do not think that science exhausts or answers everything. There is a place, and a need, for a kind of secular spirituality. Over-reliance on science and technology can lead to the kind of singularity-mongering mind-uploading techno-rapture nonsense that we see taking hold in some echo chambers these days.

I also think that being a good human being ought to involve a healthy recognition of our shared inheritance with other animals. We are special, but we are not above and beyond.

And finally, are there any Humanists UK campaigns that are close to your heart?

The humanist campaigns give me many more reasons to be humanist-friendly. I’ll pick one – the campaign to support legalisation of assisted dying. I recognise that this can be a fraught issue, because of real risks of vulnerability and implicit or explicit exploitation. But I think these risks can be handled by sufficiently robust frameworks. It is tempting to say that disenfranchising people from this most personal of decisions is profoundly dehumanising. But this would be wrong, because this is one context in which we do not extend the same cruelty to non-human animals.

What is consciousness? And could AI have it? | Professor Anil Seth | The Voltaire Lecture 2025 Hybrid

31 October 2025, 19:30

This event is now closed.