Humanist ideas and values have a global heritage as old as recorded history, but the origins of Humanists UK lie in the 19th century, an age when growing scientific understanding was challenging religious ideas, and an organised movement rooted in non-religious ethics was gaining momentum.

Under the broad umbrella of ‘freethought’, the 19th century witnessed the emergence of the positivists and their ‘religion of humanity’; the coining of ‘secularism’ and the creation of the National Secular Society; the birth of the Rationalist Press Association; and the UK growth of the Ethical movement – which would give rise to Humanists UK. Between them, these organisations had many people and causes in common.

Humanists UK traces its origins to a number of disparate organisations – humanist or ‘ethical’ societies devoted to community projects and ‘right living’ without religion, which came together as the British Humanist Association, and a ‘rationalist’ movement of freethinking publishers and pamphleteers, centred around the Rationalist Press Association, which championed free speech and scientific progress in censorious, more superstitious times.

Rational and ethical

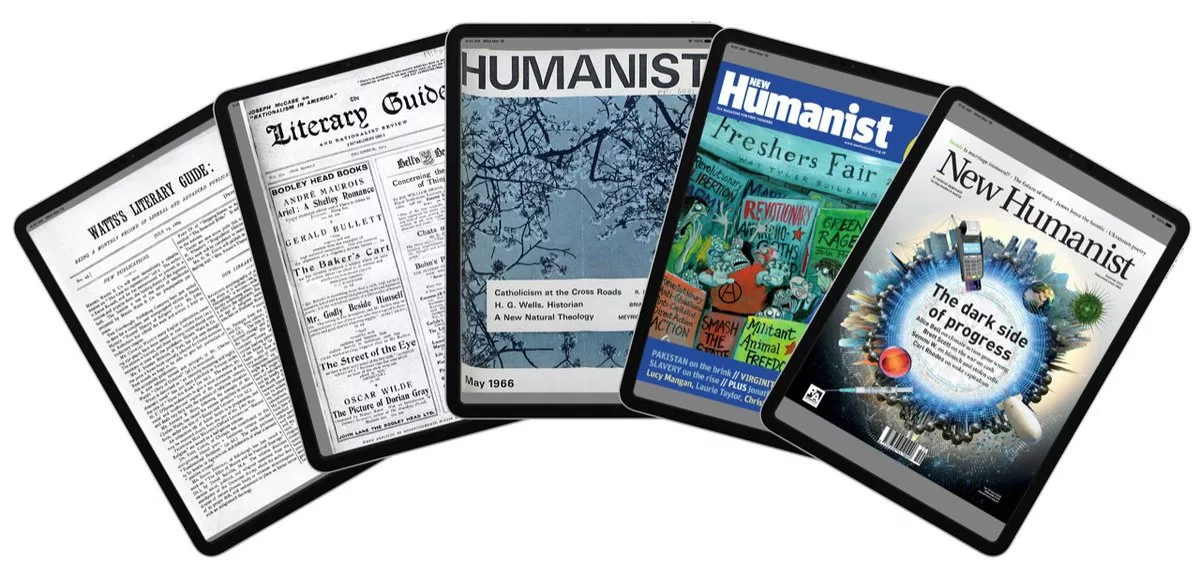

The Rationalist Press Association began life in 1889 as a ‘Propagandist Press Fund’, aiming to promote freethought publications, and to change a law which meant wills leaving money for ‘anti-theological purposes’ could be challenged, and the funds confiscated. This new scheme was the brainchild of Charles Albert Watts, who four years earlier had founded a little monthly paper called Watts’s Literary Guide, for sharing publications and reviews of interest to freethinkers.

Through flagship publications like the Agnostic Annual (later Rationalist Annual) and the Literary Guide (which became New Humanist), the RPA championed reason, science, and ethical living, attracting luminaries like Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and H.G. Wells. Significantly, pioneering series like the sixpenny reprints and Thinker’s Library, made scientific, philosophical, and freethinking works accessible and affordable–the astonishing popularity of these proving there was a public for works that many other publishers feared to print.

The Victorian ‘age of doubt’ also saw large numbers of people coming together in the latter part of the century to start up what were known as ‘ethical societies’ – early humanist societies, promoting morality without theology. In 1896, the Union of Ethical Societies was founded by four of what would become dozens of individual ethical societies. The Union emphasised ethical living free of supernatural belief.

Like the RPA, the Union published pamphlets and magazines, but its focus was more on community, including providing non-religious weddings and baby-namings, and a series of lectures on themes ranging from women’s rights and racial equality to the raising of children without religion.

Many of the movement’s leading lights were in the end active across all of the ‘rationalist’, ‘humanist’, and ‘secular’ non-religious organisations of the time, including figures such as George Jacob Holyoake (who coined the term ‘secularism’), and F.J. Gould (a pioneer of moral education). Shared causes also united this early humanist and rationalist movement, with both the RPA and the Union promoting rational thinking and ethical living, independent thought, and collective action. They grappled with social and legal issues around religious bias, freedom of belief, secular education, and human rights. The pages of the RPA’s Literary Guide would often promote the work of the Union, while the Union encouraged attendees at its lectures to subscribe to the magazine.

Into the 20th century: growth of a movement

From the turn of the century and in the decades that followed, this close relationship continued. The RPA became known as the publishing arm of the humanist movement, while the Ethical Union focused on education, but active work for a fairer society underpinned both groups – this was no armchair philosophy. There were collaborative efforts to establish the Secular Education League opposed to faith-based education, to repeal the blasphemy laws, offer humanist ceremonies for non-religious families, and encourage non-religious fellowship, as well as a number of shared conferences and campaigns over many decades.

The post-war period saw the acceleration of the now self-described humanist movement. Leaders from the ethical and rationalist branches, such as H.J. Blackham and Hector Hawton, came together to form the Humanist Council in 1950, and co-operated on a global scale in setting up the International Humanist and Ethical Union (founded 1952) and organising the first World Humanist Congress in London five years later. Meanwhile, this shared identity was reflected in print when in 1956 the Literary Guide became The Humanist. Congratulations on the change came from, among others, the philosopher Bertrand Russell and the radio presenter Margaret Knight, who viewed this as ‘a more attractive as well as a more accurate title’.

In 1963, the RPA and the Ethical Union officially came together to sponsor a joint venture known as the British Humanist Association, to be an umbrella organisation for both groups. Though successful in raising their profile and increasing their membership, this was not to last. The Ethical Union’s loss of charitable status in 1966 forced the RPA to withdraw, and the following year the Ethical Union changed its name, becoming the British Humanist Association in 1967.

A humanist revolution

The latter part of the 20th century saw the BHA flourish. Campaigns for humanist funerals, blasphemy law reform, and inclusive education gained traction. Advocacy work on LGBT rights, assisted dying, and secularism in public life further cemented the BHA’s role as a leading voice for non-religious people. In 1972, The Humanist became New Humanist, and editors like Nicolas Walter and Jim Herrick – both active across the humanist movement – worked to maintain close links between the key organisations.

As the world entered the 21st century, the BHA adapted to a changing landscape. Human rights advocacy, humanist ceremonies, and dialogue and education about humanism were joined by new specialist services to non-religious asylum seekers and people in hospitals, prisons, and the armed forces. In 2017, with a supporter base of 120,000 members and growing, the charity took the name Humanists UK and 2025 witnessed the historic merger into Humanists UK of the Rationalist Association, bringing New Humanist’s celebrated blend of insight, analysis, and high-quality journalism to an expanded circulation of over 140,000 people, and reviving the Rationalist Press as a leading publisher of books with humanist and rationalist themes.

Explore humanist and rationalist history