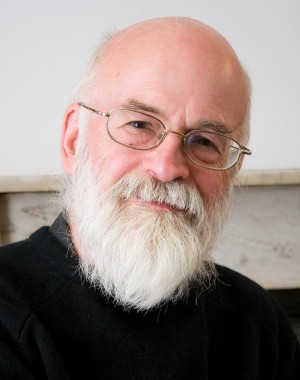

It was with great sorrow that we heard of the death of author and BHA patron Terry Pratchett. His fiction was loved by many, both children and adults, and he will be much missed.

Terry Pratchett was born in 1948 and began his career as a local journalist before becoming a Press Officer and then in 1987 a full-time writer. His first fantasy novel was The Carpet People in 1971, and in 1983 The Colour of Magic was the first in his humorous Discworld series. His novels, while always being highly entertaining, often had a serious or satirical element and in many he dealt with philosophical and ethical questions and arguments, touching on topics such as religion, consciousness and international relations. When he won the Carnegie Medal in 2001, he said: ‘Far more beguiling to me than the idea that evil can be destroyed by throwing a piece of expensive costume jewellery into a volcano is the possibility that peace between nations can be maintained by careful diplomacy.’ In 1998 he was made an OBE for his services to literature.

Like many humanists, he was also interested in science, and with Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen wrote four books using his Discworld series to illustrate popular science topics.

In December 2007 he announced, with typical humour and stoicism, ‘An Embuggerance’: that he had been diagnosed with a very rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s. ‘We are taking it fairly philosophically down here and possibly with a mild optimism,’ he wrote. ‘…I would just like to draw attention to everyone reading the above that this should be interpreted as “I am not dead”. I will, of course, be dead at some future point, as will everybody else. For me, this may be further off than you think – it’s too soon to tell. I know it’s a very human thing to say “Is there anything I can do,” but in this case I would only entertain offers from very high-end experts in brain chemistry.’

He devoted much of the rest of his life to raising awareness of dementia and the urgent need for more research. He also explored the case for assisted suicide in a much discussed television documentary.

In 2013, Terry was awarded the BHA’s Humanist of the Year award at its Annual Conference, on which occasion he was praised for the way in which he had turned his personal suffering into a positive campaign: firstly to fund greater research into Alzheimer’s disease and secondly for the right to die with dignity. He had an enormous impact on the public debate around that issue and showcased humanist values in doing so. His support for the right to die was inextricably linked to his Humanism and his belief in the essential dignity and rightful autonomy of human beings. He said:

‘People with locked in syndrome who wish to die are not allowed to. Why? Because they are prisoners of God and in Tony [Nicklinson]’s case, even worse, prisoners of technology which can keep them alive against their wishes. I apparently live in a democracy, but I never voted for God and yet God’s vote means that stricken Britons are invited to trudge to other countries to die. I wish I could give you a few funny lines about God, but he wouldn’t like it. Every poll shows that the people of this country would support assisted dying under safeguards such as used in many places elsewhere in the world, but not Britain because God doesn’t want it.’

Terry was also a keen promoter of Humanism in schools, and was regularly filmed from the 1990s until recently for the BHA’s school resources website, talking about humanist values and ethical perspectives.

Even as his health continued to fail, Terry continued to be highly involved with the BHA and with humanist causes. As recently as 2014, he was one of more than 100 signatories who wrote to David Cameron challenging his use of divisive rhetoric in claiming superior status for Christianity in British national life. That same year, Terry also contributed to the BHA-supported legal case of Tony Nicklinson and Paul Lamb for their right to die. In that submission, he wrote:

‘…I have no difficulty, for example, and have said this publicly, with the idea that should you, in the course of your old age, reach a point where it would be sensible for you to be switched off, rather than leave with machinery more or less keeping going, I see no problem with that whatsoever. It seems to me the flipside of the fact that we now live to a great age, quite often in reasonable health throughout, because of what we have been able to do over the years because of our continued understanding of how the universe works, and what our place in it can be… And, so possibly, when medicine can’t do any more, and life does become either so much of a burden as not to be borne, or indeed possibly not even quite there in a way we would understand it, that an easeful death should be arranged.’

Powerfully, he appealed ‘Either we have control of our lives, or we do not.’

He was keen to stress his support for Humanism wherever possible. In his Humanist of the Year acceptance speech, he said:

‘Every time I hear somebody say the words “as a Christian…” I always reply “as an atheist” and I believe that most people in this country are, even if they do not articulate it.’

Commenting on Terry’s death, BHA Chief Executive Andrew Copson said:

‘Terry was a great humanist and stalwart supporter of our work for a fairer society. He will be missed by all of us who worked with him on the causes he cared about and our thoughts are with his family and friends at this time.

‘Terry had a tremendous gift of giving life to stories of great wonder, richness, humanity and warmth, for which many people all over the world will remember him. He had a great heart as well. Joy, suffering, happiness, the whole of the human experience: his stories captured all of this and much besides with good humour, and he turned these same talents to providing for a better future for generations to come, through his steadfast work to promote Humanism and a compassionate assisted dying law.

‘We at the BHA continue to be grateful for all his tireless support, a gratitude we share with all those he reached through his stories and to whom he gave hope through his campaigning.’

Notes

For further information or contact, please call Andrew Copson on 020 3675 0959 or email him on andrew@humanists.uk.