Following on from polls showing that even Church of England priests accept that the UK is no longer a ‘Christian country’, there have been articles in some newspapers lamenting this fact and saying it has something to do with the supposedly sorry state of the world today.

The gloomy argument in these papers runs like this: all the problems of the UK today can be laid at the door of secularisation. They claim that life in the UK is unspeakably bleak today compared to halcyon days in a bygone decade when religious participation was high and identification with the national church near-total.

After all, the decline of religion in the UK has been dramatic. Today 53% of adults claim no religion, and just 12% identify with the established church.

But there’s just one problem. That whole narrative of social decline? It’s pure nonsense.

Secularisation and the caring society

The truth is that, despite all its problems, and accepting that new problems arise and will continue to arise all the time in every society on Earth, life in the UK is still – recent global political and economic turmoil aside – in a much better shape now than in any previous era of history.

That goes doubly for ethnic minorities, for LGBT people, for people with disabilities, and for people with mental health conditions or any variety of neurodivergence. The public today is more concerned with human rights, and with equality of both outcome and opportunity, than at any other time in British history.

Don’t let the naysayers have you fooled by a factitious picture of moral decline, holding up all the most troubling statistics on the Government’s list of problems-to-deal-with as their ‘proof’.

Because if there has been a moral or social change in the British public writ large, it has been the enlargement of our moral compass, the widening of our empathy, and a growth in the public’s commitment to fairness and justice.

The not-so-lovely past

For ‘evidence’ of moral and social decline caused by the ‘banishing’ of Christianity, Rod Liddle in the Times cited the UK’s divorce rates – higher now than in the past– while Celia Walden in the Telegraph pointed to an uptick in teenage mental health referrals in the past decade, along with an increase in men and women going to the gym or a pilates class as their preferred pastimes.

Now, if ever there was a time when Britain was undeniably a Christian country, that time was the 1940s and 1950s.

These were terrible times to be alive. Putting poverty and steep inflation to one side (sounds familiar…), this was a time when women could not have abortions, seek out birth control, open a bank account independently of a man, or expect to be hired into a ‘man’s job’. It was a time when homosexual acts were illegal, and so LGBT people lived lives of repression, under constant threat of exposure and persecution from the police. A time when racism was openly preached and practised across all newspapers and government departments. And when religion so predominated our lives that the airwaves were scrubbed clean of even the slightest whiff of irreligion, with humanists like Margaret Knight hounded and vilified for even suggesting on the radio that such a thing as morals without religion could exist.

What we do not have, for this past era, are reliable rates of domestic abuse (undoubtedly very high) or hate crime to cite. And we cannot quantify the economic or social cost to society from holding back many of the best and brightest on grounds of sex or race or disability or religion or belief. But this unaccounted cost is certain to have been intolerably, despairingly vast. The UK was a far less tolerant place. These were not better times for anyone.

Humanists UK’s own archives testify to this in great detail. The 1950s were a time of pressing activism at Humanists UK, and humanists were hard at work putting together networks, agitating for an ‘open conspiracy’ to improve the world, make better the lives for minorities, and win some breathing room from the oppressive yoke of religion.

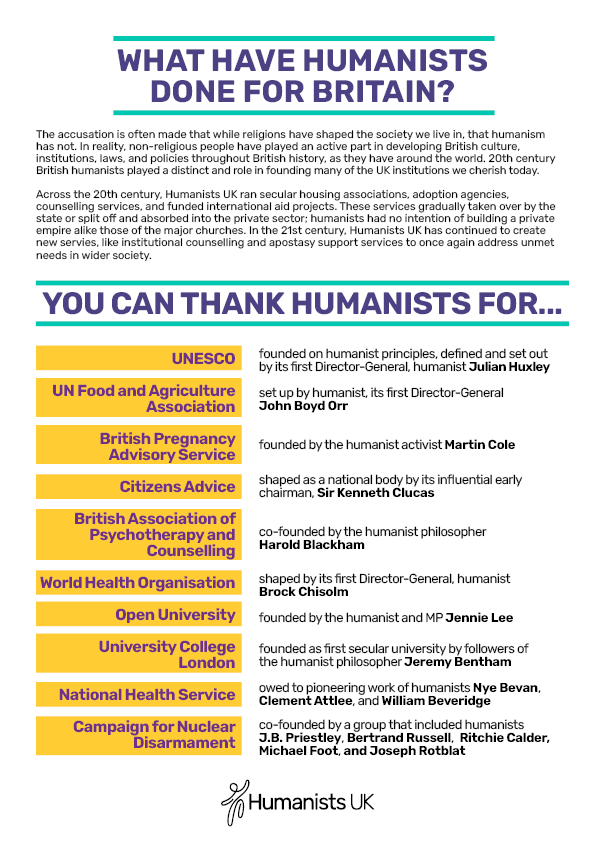

The world has since come along a long way, in part by their efforts. On the political scene, humanists MPs like Nye Bevan and Clement Attlee, and thinkers like William Beveridge – a second-generation humanist — sought to address the inadequacies of the time with new and imaginative approaches like the NHS. The list of institutions we take for granted today that derive explicitly from humanist programmes, plans, and activism – from the Open University to the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy – is immense. And it cuts against any narrative of moral freefall against the backdrop of religious collapse.

Every generation says the same thing…

Even in the supposedly harmonious 1950s, the same narrative of steep social decline was regularly trotted out. Historians have tracked with amusement, right back to fragmentary writings from Ancient Greece and Ancient China, how every generation without exception has lambasted the tastes of young people and found a litany of things going wrong to conclude that they now lived in the worst time in human history.

Before pundits were dismayed about Gen Z watching makeup tutorials on TikTok, they were dismayed about millennials choosing to eat avocado on toast, or Gen Xers enjoying late-night parties and dancing to house music, and about Baby Boomers wearing flared trousers and discovering Motown. The sky never fell in on any of them. Fashions and trends change all the time. Plus ça change.

In his day, Socrates had certainly had enough of today’s kids. He said:

‘Children; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. They no longer rise when elders enter the room, they contradict their parents and tyrannise their teachers. Children are now tyrants.’

To those who think now as Socrates did then, a study of American young adults (‘Gen Z’) from McKinsey suggested that as well as being uniquely skilled for the workplaces of the future, this generation was more idealistic, less materialistic, and even by some measures less ‘self-centred’ than their older siblings, parents, or grandparents. When it comes to the supposed signs of social decay of yesteryear – like watching too much TV, or binge drinking, or drug use – Gen Z is turning them down. Yet the narrative of social collapse continues. We have much to be optimistic about when this caring, thoughtful generation takes the reins!

In Britain, a mere 0.7% of adults aged 18-24 identify with the Church of England. The data certainly predicts a very steep decline for Anglicanism and from religion as a whole. But while the Telegraph claims this shows young people instead now worship the ‘cult of self’, the actual evidence seems to suggest the precise opposite to be true.

The state of the world: war, disease, and poverty

Of course, saying the world is getting better when we are all living through a time of high inflation on household goods and the crushing effect of high interest rates could feel like a slap in the face. But laying out all the causes of the UK’s current economic dysfunction (Brexit and Covid both hit in 2020, along with the war in Ukraine in 2022), even looking back decades, blame certainly can’t be placed on secularisation of all things.

When people look in horror at politicians serving dehumanising rhetoric towards those seeking refuge in the UK, we cannot explain this in terms of religion or irreligion either. Any cursory look at Hansard in Parliament will show that the opposition to such cruelty unites people of conscience of all backgrounds, including humanists very prominently.

We should be careful not to mistake for long-term decline what can be more charitably explained in terms of recent political failures (whether that’s schools collapsing or five-year NHS waiting lists). There is no obvious causal link between how religious a country is, whether it elects good politicians, and if the governments it elects invests in the right places at the right time. A few global studies do show some correlation between highly secularised countries and strong social safety nets, high levels of equality, peacefulness, and other markers of progress, as we find in Scandinavia. The UK conforms to these global trend lines very well, which may bode well for the future.

Organisations like Humanists UK have been as active as anyone in identifying and talking about urgent social problems facing the world, from a resurgence in authoritarian populism to the climate crisis. These are global problems which demand sustained attention. But they are no more linked to emptying out of Anglican pews over the last 100 years than they are to the steep decline of piracy in the last 300.

There can be no doubt that life in the UK has been better, fairer, and kinder to more people in the 21st century than at any time in the 20th. Without sounding triumphalist, humanists can take a lot of pride in that, because we have played a large role in bringing about positive social and cultural change, working alongside people of good conscience from other beliefs as often as we can.

Kindness; looking for evidence; imagining how other people want to be treated; and making this the basis of your morality… What seemed outrageous in Humanists UK pamphlets in 1950 now sounds almost anodyne to some. The response we hear when exhibiting for Humanists UK at party conferences or explaining to strangers what we do for a living is sometimes ‘But aren’t these the values most people live by?’

If that is true today, it certainly wasn’t true for most of history. Humanists UK’s job is to represent, advocate, and speak up for the values of the non-religious – humanist values – in our public debate. Our campaigns for equality, human rights, freedom of thought, freedom of choice, and freedom of expression are grounded in these same ethical values.

The project of building a better, fairer world might never be over. There is a dizzying amount of work to do. But to those who look at long-term demographic change aghast and horrified, let us say just this: cheer up! You have everything to be happy about.

Or as the humanist activist Robert G. Ingersoll once put it:

The time to be happy is now; the place to be happy is here; and the way to be happy is to make others so.